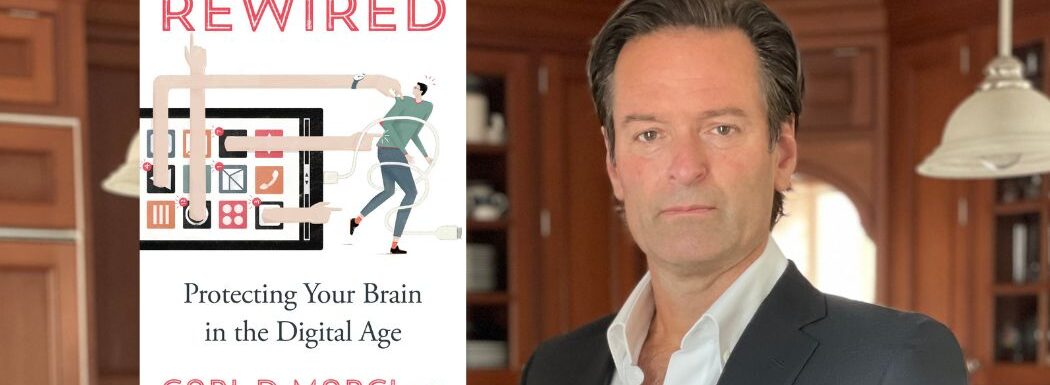

In this podcast episode, Roger Dooley welcomes Dr. Carl Marci, a pioneer in the neuromarketing space. They discuss Dr. Marci’s current work in healthcare and technology, his views on tech-life balance, and the state of the neuromarketing industry. Dr. Marci emphasizes the need for a balance between reducing friction and maintaining human interaction in the digital age. He also discusses the importance of battery life, signal quality, and open access in measurement devices. The conversation then shifts to Dr. Marci’s book, REWIRED: Protecting Your Brain in the Digital Age, which focuses on protecting the brain from the negative impacts of technology. They explore the effects of media multitasking, distracted driving, and generative AI. Dr. Marci highlights the concept of super stimuli and its impact on our behavior, particularly in relation to social media. He emphasizes the need for responsible use of technology and understanding the fine line between habit and addiction.

In this podcast episode, Roger Dooley welcomes Dr. Carl Marci, a pioneer in the neuromarketing space. They discuss Dr. Marci’s current work in healthcare and technology, his views on tech-life balance, and the state of the neuromarketing industry. Dr. Marci emphasizes the need for a balance between reducing friction and maintaining human interaction in the digital age. He also discusses the importance of battery life, signal quality, and open access in measurement devices. The conversation then shifts to Dr. Marci’s book, REWIRED: Protecting Your Brain in the Digital Age, which focuses on protecting the brain from the negative impacts of technology. They explore the effects of media multitasking, distracted driving, and generative AI. Dr. Marci highlights the concept of super stimuli and its impact on our behavior, particularly in relation to social media. He emphasizes the need for responsible use of technology and understanding the fine line between habit and addiction.

Listen In

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Carl Marci – Key Moments

Tech-life balance and reducing social interaction [00:02:31] Dr. Marci discusses the need for a balance between reducing friction and maintaining social interaction in the digital age.

Friction in self-checkout and customer choice [00:03:38] The speakers discuss their preferences and frustrations with self-checkout systems and the importance of having a choice between human interaction and convenience.

Challenges and future of the neuromarketing industry [00:06:23] Dr. Marci shares his perspective on the challenges of scaling the neuromarketing industry and the potential for AI and data to be the solution.

Battery life and signal quality [00:08:16] Discussion on the trade-offs between small, nice-looking measurement devices and the quality of the signal and access to data.

The book “Rewired” and protecting the brain [00:09:18] Dr. Marci’s motivation for writing the book and his observations on the negative impacts of technology on mental health.

Media multitasking and its effects [00:13:04] The consequences of media multitasking, including decreased processing speed, increased error rate, anxiety, depression, and lower grades.

The rise of distractions in the car [00:16:20] Discusses the increase in car accidents due to distractions and the need for laws and education to address the issue.

The introduction of the automobile and the need for stop signs [00:17:23] Compares the introduction of automobiles to the current technology landscape and emphasizes the need for “stop signs” on the information superhighway.

The potential of generative AI and immersive conversations [00:18:27] Explores the possibilities of conversing with AI bots or historical figures and the impact it may have on human interactions.

Super stimuli and its impact on behavior [00:24:46] Certain stimuli can override innate needs, leading to behavior that prioritizes artificial versions of those stimuli. Examples include songbirds and beetles.

The influence of curated super stimuli [00:25:45] Surgically enhanced women, luscious food photos, and social media filters create curated super stimuli that are difficult for the brain to ignore, leading to potential issues.

Finding Dr. Carl Marci online [00:26:43] Dr. Carl Marci can be found on his website “Rewired the Book” and on LinkedIn. His book can be purchased on Amazon or most bookstores.

Carl Marci Quotes

The Difference Between Big Companies and Early Stage Companies:

“In a big company, when there’s a fire, you have a meeting to talk about the fire, you have another meeting to talk about maybe whether we should wait a little bit longer to put the fire out. You have a third meeting to talk about whose fault it was. And in between, there’s a lot of finger pointing. In an early stage company, if there’s a fire, you put it out.”

— Carl Marci [00:01:47 → 00:02:05]

The Importance of Tech Life Balance:

It’s the point of the book, which is we need to have tech life balance, right?”

— Carl Marci [00:03:04 → 00:03:11]

The Future of AI in Media Research:

“I’m not sure that we’ve cracked the code in terms of what’s the killer application that balances high quality sensors, great science with an application that’s repeatable scalable and that customers are delighted with.”

— Carl Marci [00:07:23 → 00:07:40]

The Future of Wearable Technology:

“I do think that’s where another kind of convergence is happening. There’s some very small, nice looking technologies that do a good job, and applying those and having entrepreneurs apply those in different ways, I think, is absolutely going to be part of the future as they become more and more ubiquitous, right. More and more people using and wearing smartwatches and all kinds of sensor devices, eventually there’s going to be a big data play on all those sensors, and then you’re going to start to mine that in different ways. That’s likely where this goes.”

— Carl Marci [00:09:18 → 00:09:50]

The Impact of Social Media Addiction:

“I was like, she doesn’t look that good… I don’t think she’s going to make it in less than ten minutes in this study… And all I could do and associate in my mind was to B. F. Skinner… That looks an awful lot like withdrawal symptoms to a technology that everyone’s using. Is that concerning?”

— Carl Marci [00:11:18 → 00:11:23]

The Dangers of Media Multitasking:

“The more you do it, the more you build this habit…the higher rates of anxiety and depression. You have decreased attention spans. You have increased impulsivity. And for kids who are school age, you have lower grades and lower test scores across the board.”

— Carl Marci [00:14:35 → 00:14:50]

Distractions in the Car:

“For 40 years, the number of deaths per mile in this country were going down, right? Better lighting, better signage, better brakes, airbags sensors of all types. Until 2016 and every year since 2016, it’s actually starting to creep up. The number one reason is distractions in the car.”

— Carl Marci [00:16:55 → 00:17:18]

The Impact of Technology on Mental Health:

“And I heard this the other day, and I’m still trying to get my head around it. From roughly 2000 to 2020, the number of adult Americans who reported that they do not have a confidant or best friend in their life went from 2% to 12%. That’s a ten-time increase, almost.”

— Carl Marci [00:24:08 → 00:24:28]

The Impact of Super Stimuli on the Brain:

“The filters of social media create these curated super stimuli that are very hard for the brain to ignore… that is driving a lot of these issues.”

— Carl Marci [00:26:31 → 00:26:45]

About Carl Marci

Dr. Carl D. Marci is physician, neuroscientist, author and entrepreneur. He is currently a Chief Psychiatrist and Managing Director of Mental Health and Neuroscience at OM1, a ventured-backed health technology real-world data company. He is also part-time staff psychiatrist at MGH and part-time Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Marci has worked at multiple early stage health technology and mental health delivery companies in the past. He has extensive training health research, the use of biological measures and the neuroscience of emotion through two National Institutes of Health fellowships. He holds seven US patents, has published numerous articles in peer-reviewed science journals, gives lectures regionally, nationally, and internationally and is a leader in the fields of social & consumer neuroscience and digital health. Dr. Marci is also a Henry Crown Fellow at the Aspen Institute and is a member of the Aspen Global Leadership Network.

Carl Marci Resources

Amazon: REWIRED: Protecting Your Brain in the Digital Age

Twitter: @CMBiometrics

LinkedIn: Carl D. Marci, M.D.

Website: www.rewiredthebook.com

Share the Love:

If you like Brainfluence…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Transcript:

Full Episode Transcript PDF: Click HERE

Intro [00:00:00]:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley shares powerful but practical ideas from world class experts and sometimes a few of his own. To learn more about Roger’s books, Brainfluence, and Friction, and to find links to his latest articles and videos, the best place to start is RogerDooley.com. Roger’s keynotes will keep your audience entertained and engaged. At the same time, he will change the way they think about customer and employee experience. To check availability for an in person or virtual keynote or workshop, visit RogerDooley.com.

Roger Dooley [00:00:38]:

Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley. Today we welcome back Dr. Carl Marci. Carl has been a pioneer in the neuromarketing space since his founding of Interscope Research in 2006. He later served as chief neuroscientist at Nielsen Consumer Neuroscience. He’s long been associated with Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital. Today, he describes himself as a physician, scientist, entrepreneur, and author. His recent book is Rewired: Protecting Your Brain in the Digital Age. Welcome to the show, Carl.

Carl Marci [00:01:08]:

Roger, it’s great to see you again, and thanks for having me.

Roger Dooley [00:01:10]:

Well, really wonderful to have you back. You know, Carl, your resume is pretty complicated these days. Just glancing at your LinkedIn profile, how do you spend what’s a typical day look like for you now?

Carl Marci [00:01:22]:

Yeah, it’s a good question. So I’ve really enjoyed the transition from consumer neuroscience to healthcare, which is very different in many ways, as you can imagine. And I’ve had a series of early stage company experiences, and I find that’s really what I enjoy. I like to tell people I’ve worked in big companies and I’ve worked in early stage companies. And the difference is, in a big company, when there’s a fire, you have a meeting to talk about the fire, you have another meeting to talk about maybe whether we should wait a little bit longer to put the fire out. You have a third meeting to talk about whose fault it was. And in between, there’s a lot of finger pointing. In an early stage company, if there’s a fire, you put it out. So I prefer to put out fires, and I like having that influence. So I advise companies on the side. I do some investing in early stage health and technology companies, and then I am the managing director and chief psychiatrist for a health and data technology company called Om One. So trying to organize healthcare data and use it to help get better outcomes for life science companies and large hospital networks.

Roger Dooley [00:02:31]:

That really sounds fascinating, like, you’re really filling up your days with cool stuff, and I can’t wait to see what new innovations come out of Carl. You know, I was looking at what you’ve been writing recently, and just a month or two ago, you wrote an article in The Wall Street Journal, which was titled, something like, what we Lose when Companies Make Things Easier for Customers. Now, my message in my most recent book and most of my speeches is how companies should make things easier for their customers. So are we going to fight here or explain your point of view?

Carl Marci [00:03:04]:

No, I think honestly, it’s the point of the book, which is we need to have tech life balance, right? And so there’s clearly things in the world where you want to reduce friction because it’s unnecessary. But when we reduce it to the point where there’s zero social interaction or human interaction, you do start to deprive the brain of something we evolved over a million years to do, which is interact the way we you know I bristle when I go to CVS in Boston and there’s nobody at the checkout counter, and I’ve got to use the machine, right? And I’ll just purposely push the button and make someone come over so I can say hello and have that kind of, don’t worry, Carl.

Roger Dooley [00:03:43]:

Nobody’s nobody’s listening.

Carl Marci [00:03:44]:

Exactly. I think there are times when that makes a lot of, like, you know, I go to the gas station. I don’t need a human. I put my card in and I check it out and I’m on my way. So I think there’s a balance here somewhere. And I think when everyone and the data is showing this spends time not doing social interaction, that begins to deprive the brain of something it needs. And that was really the point of the article. Have we gone too far?

Roger Dooley [00:04:09]:

That’s all right. And I’m with you on your example of self checkout is perfect. Often I have a choice in what I’m checking out in the store. There are some regular checkout lanes with cashiers that are open and maybe self checkout lane that’s open. If I’ve got two or three items that I know are clearly barcoded, I’m going to go for the self checkout. Every time. I don’t have to interact. I just do my thing and I’m done. In fact, I love it now that at Whole Foods, they have Amazon One for payment where I don’t have to get out an app, I don’t have to get my phone for an app, I don’t have to get out my wallet for a credit card. I just put my Palm over the reader and I’m checked out, and I can literally do a grocery transaction, probably 30 seconds or less. And that’s really fun and amazing. But on the other hand, if I’ve done a week’s worth of shopping and I’ve got all kinds of produce that needs to be weighed, and whatnot with encodes entered, I definitely want a human to help me with that. So it irritates me when stores try and push you into whatever choice they prefer, which is typically the lower cost for them. The self checkout, I think it’s great that they offer it, but when they start forcing you into it because they have one cashier and the line is ten people deep, that’s not good.

Carl Marci [00:05:19]:

Now I’ll give you another example where there’s a lot of friction that we need to remove. And that’s with healthcare records, right? The interface clinicians entering data in. I mean, it’s literally 2030 year old technology that needs to be updated. But that’s hard to do because these systems, they get really baked in so that it’s hard to change. Yeah. And who doesn’t like the experience on Amazon being click click and I’m done. That’s a great example where there’s no need for humans and there’s no need for friction.

Roger Dooley [00:05:50]:

I suppose an example of maybe not so good lack of friction would be Netflix starting the next show immediately. So you don’t actually have to make a conscious choice to watch the next episode. Just sit there for a few seconds and it’s going to go. And would you agree with, you know.

Carl Marci [00:06:07]:

I’m associating in my mind to my children who love watching YouTube or Netflix, and that autoplay literally just makes their little brain want to watch more. And so I have to say, okay, guys, this is the last episode. Only a few more minutes left in this episode. We’re really going to go after this episode, right? Because as soon as the next one starts, you can’t tear them away. It’s that powerful.

Roger Dooley [00:06:32]:

Just wait until the end of this, dad. It’ll be over.

Carl Marci [00:06:34]:

Honestly, I always fail. They’re like, well, just one more. OK, one more. But then that’s definitely it.

Roger Dooley [00:06:39]:

Yeah. Carl, you’ve been out of the neuromarketing space for a while, but I’m curious what you would make of it now in this sort of post pandemic period. A lot of stuff happened during the pandemic. A lot of labs closed. And whatnot, what’s your sort of take on the state of the neuromarketing industry?

Carl Marci [00:06:55]:

Yeah, I’m out of it, so I have a very outside perspective. I think one of the challenges of the model was how do you scale it? Labs are terrific, but they have a lot of overhead and you have to use them at a certain capacity and you have to keep going. And you’re constantly interacting with the public. And the sensors are complex and they break and they have to be handled with a particular kind of care. So I’m not sure that we’ve cracked the code in terms of what’s the killer application that balances high quality sensors, great science with an application that’s repeatable scalable and that customers are delighted with. And I think that’ll come. And I think all the chatter about AI and some combination of data and consumer neuroscience technology is probably going to be that solution. But for now, it continues, as far as I can tell, to do what it’s always done, which is play in particular areas where there’s no other tools in market and media research to answer the questions. And I think that’s a very reasonable niche and that will be there for a long time.

Roger Dooley [00:08:06]:

From the early days at Interscope, I know that you emphasized a fairly simple approach to collecting data, which was using biometrics as opposed to complicated, either EEGs with sort of big arrays of electrodes, or fMRI, which is, of course, very expensive and not all that practical. I’m curious now what you make of the new smartwatch based neuromarketing techniques and whether you think that type of measurement can provide data that’s at least somewhat useful and somewhat predictive.

Carl Marci [00:08:42]:

Yeah, I think we’re getting there, and it’s a step in the right direction. Right. But again, you got to trade off. Let’s get technical for a second. Battery life, signal quality, open access so that you know what the algorithms are and the ability to manage data and put your own algorithms to it, but have those be able to stand up to scientific scrutiny. But I always said the smaller and nicer looking the measurement device, the bigger the trade off in terms of the quality of the signal, your ability to access and do what you want to it. So you got to play that off. I do think that’s where another kind of convergence is happening. There’s some very small, nice looking technologies that do a good job, and applying those and having entrepreneurs apply those in different ways, I think, is absolutely going to be part of the future as they become more and more ubiquitous, right. More and more people using and wearing smartwatches and all kinds of sensor devices, eventually there’s going to be a big data play on all those sensors, and then you’re going to start to mine that in different ways. And that’s likely where this goes.

Roger Dooley [00:09:50]:

Carl, let’s talk a little bit about the book Rewired. It’s about protecting your brain. It seems kind of like you’ve switched teams here from sort of helping companies understand customer brains to market to them better. And this is really for the other side of the equation, the consumer of anything, media, whatever, protecting their brains. What caused you to write this book? I was surprised, as far as I could tell, from Amazon. This is your first book. What made you want finally to write this book?

Carl Marci [00:10:23]:

It’s a great question, and I talk a little bit about this in the introduction, this story. We were at the Time Warner Media Lab, and this is 2011, and we were doing a study on young women who were heavy users of social media. And they were recruited, and we randomized them very simply into two conditions. Watch TV at home like you would at home, but in our lab so you can have your smartphone. And of course, they all did, and they’re watching TV and they’re just being censored. And in the other condition, we just asked, we’re going to take your smartphone, we’re going to put it on the table outside so you could watch like you would at home, except without this second screen. And we didn’t realize at the time that that’s a deprivation study is what we would call it now, because nobody thought that that’s actually what it was. And I’ll never forget watching the first young woman in the study without the smartphone, sitting on the couch. And she starts to sort of shake a little bit, and she’s going back and forth, and I’m watching her. I was like, she doesn’t look that good. And I was like, I don’t think she’s going to make it in less than ten minutes in this study. She gets up, grabs her phone, and runs out of the lab. And I went out and said, Is everything okay? Yeah, she just left. Okay, next young girl comes in, does the same thing. Next one, same thing. And we lost a third of the participants in that group. And all I could do and associate in my mind was to BF. Skinner. Remember him? The father of behavioral psychology? And the Skinner rats in a box that you get them hooked on. They have a choice between sugar water and cocaine water, and they get hooked on the cocaine water, and then you take the cocaine away and they start to go into withdrawal and they move around. That was the first descriptions of behavioral withdrawal from something you’re addicted to. And in my psychiatrist head, I said, you know what? That looks an awful lot like withdrawal symptoms to a technology that everyone’s using. Is that concerning? And so after that, I started just take notes here and there, collect a reference. And the more I did that, the more intrigued I became and the more concerned I became that this is starting to have the kinds of impacts we’re all talking about now in terms of anxiety, depression, substance use, loneliness, tragically suicide, ADHD increasing in low double digits in almost every age group. In direct parallel with the penetration of this technology, social media and other applications becomes very concerning.

Roger Dooley [00:12:43]:

That’s getting into the multitasking area that you talk about quite a bit, Carl, where somebody is simultaneously using at least two devices, perhaps watching something on a big screen while using a tablet or a phone in their hand. And I have to make a confession. I often do that myself, depending on the content in each case. For example, right now we’re in football season. If I’m watching a football game on TV, there is a lot of downtime in that to sit there glued to the TV would actually be kind of boring most of the time because, as you know, the actual plays are relatively brief with breaks in between and commercials and everything else. On the other hand, if I was watching Top Gun Maverick, an exciting and really engaging movie there, I would probably not be inclined to be playing on my phone or tablet. Is multitasking necessarily bad?

Carl Marci [00:13:36]:

So let’s define terms. Right? So I describe media multitasking as a component of multitasking in general, and media multitasking, you gave some great examples, but it also could be, say, doing homework and checking social media, right? Or being on zoom at work and checking your email. You’re asking the right question. Doesn’t everybody do that well during the pandemic? Everybody does. And guess what? Productivity is down across the board. So what the multitasking literature shows consistently over and over and over again, is two things. One, you have decreased processing speed and increased error rate. So let’s do that again directly. Leads to decreased processing speed and increased error rate. And then what the research begins to show is the more you do it, the more you build this habit, which you just described. And by the way, we all do it to some degree, but the more you do it, the more you media multitask. So media and some other task or two media tasks, the higher rates of anxiety and depression, you have decreased attention spans, you have increased impulsivity. And for kids who are school age, you have lower grades and lower test scores across the board. To just give you an example. And this isn’t even multitasking. It’s the power of these devices which we’re all carrying around the supercomputer in our pocket. There’s a beautiful study I talk about in the book where they took young college age students and gave them a hard math test, like a standardized test. And there were three conditions, right? One was leave your phone outside the second one and turn it off. The second one was bring your phone in, turn it off, but put it under your chair. And then the third one was turn your phone off, put it on the table upside down. So upside down, under the chair and outside the room. And the results, the scores were a step function. The closer that phone came to the visual field and into your conscious awareness, the lower your test scores were. There’s other studies where just putting a phone and it doesn’t even have to be your phone, just anybody’s phone on a table, interrupts social interaction. So this idea that the technology is so powerful that it immediately draws our attention at some level, typically a non conscious level, and gives some resources to what’s there. That fear of missing out or the compulsion to react to every app ping and message ring is incredibly powerful because it’s rewiring our brains and triggering the reward system and triggering the emotion system in a way that’s powerfully reinforcing. So no, not all multitasking is bad. Like if I’m listening to the news or a podcast and I’m folding my laundry light multitasking, right? No one’s going to die. I’m not going to lose my job. My productivity is not going to suffer. But if I’m driving a car and there’s a text and I look at it, that’s a whole different ballgame. And so I think we need to be very mindful of when we’re multitasking, what’s driving it and what the risks are, right?

Roger Dooley [00:16:43]:

Well, I guess this be a time for a PSA that anybody who happens to be listening while they are driving a car or operating machinery, please pay primary attention to what you’re doing.

Carl Marci [00:16:52]:

Yeah, please do. And I talk about this in the book. For 40 years, the number of deaths per mile in this country were going down, right? Better lighting, better signage, better brakes, airbags sensors of all types. Until 2016 and every year since 2016, it’s actually starting to creep up. The number one reason is distractions in the car. So this is a great example of where governments are starting to take notice. This is a real public health and safety issue. Laws are being passed, and there’s an attempt to educate the public and change behaviors back. To push the analogy, I used the introduction of another technology in Detroit in 1908, and that’s the introduction of the automobile. Right? So the Model T rolls off the assembly line in Detroit. Detroit becomes a test bed for this new technology. They have more cars per capita than any other city in the world, and it’s a disaster. A lot of people died, children died, farmers were upset, cows are running around. It was total chaos. It took ten years before the first stop sign was put in place. It was another three years before the patent for the stop light was even issued. Right. This takes time, and I think part of what I’m trying to do is raise awareness to say, look, we just need some stop signs on the information superhighway to think a little bit about what we’re doing to ourselves.

Roger Dooley [00:18:23]:

Interesting analogy. I guess horses would not generally walk into other horses between the two of them. They would figure it out as opposed to simply colliding. But that’s a good analogy, Carl. I like that. One thing I was thinking about as I was reading the book was something that really has just sort of blown up in the last month or so, and that is generative AI or commonly or the most common app we hear about is Chat GPT. And mainly it’s in the context of either students cheating on essays or people writing reams of bad web content for SEO purposes. But it occurs to me that in terms of something that’s immersive and distracting, this could really be significant from the standpoint of the ideas in your book, where just imagine a conversation partner who perhaps is very attractive and seems very interested in you. And right now it’s mostly text. But there are also I’ve seen some nascent video things that are actually quite good. So we’re probably very close to something like that, where you could be having a human conversation with a bot or perhaps have a conversation with Albert Einstein, if that was what you wanted to. You know, you could probably get again. It isn’t here today, but I don’t think it’s going to be even five years before we’re at the point where this is really not only a thing, but actually pretty high quality. What do you think about the possibilities there? Do you agree or am I too pessimistic? Or maybe it’s no, that could be fun too.

Carl Marci [00:19:59]:

And it’s a great example of the conclusion of the book, which is look, at the end of the day, technology is a tool, right? A knife in the hands of a surgeon is a tool for healing. A knife in the hands of a murderer is a tool for death and destruction. Right? So it’s about intent. If the intent of these tools is to facilitate humans by making introductions for people who are shy a little easier or creating drafts for proposals and writing that we then take and take to the next level in a way that computers can’t do or help. People who are lonely and need interactions and for whatever reason can’t connect with real humans. There’s a role for all of that. But I think where we go off the guardrails is when you’re doing that to the exclusion of the types of interactions that we know the brain has evolved over a million years to want and need and this is the real trick. Right. I’m very careful, as you know, in the book, making a distinction between habit and addiction. But I think there’s a very fine line there. We’re all changing our habits around mobile information, communications and media technologies but that doesn’t mean we’re all addicted but we’re all getting some reward because we’re changing our habits and that we don’t develop habits that aren’t rewarding. And it’s very fine line to understand when our behaviors have tipped into something else. That’s why I keep going back to the car, because I think we can all understand a habit that we develop in our living rooms watching football on a Saturday, because there’s a lot of timeouts and commercials and it’s kind of boring. That’s developing and using media as a mood regulator. Right. Which is something we saw at Interscope all the time. People get bored, they switch devices or they pick up their phone. But when that same habit moves into the workplace and you’re no longer able to be as productive as you want or the schoolroom, and you’re no longer learned the way you need to or the car, and you’re not paying attention, you’re driving, that’s when we’ve crossed the line. And I think we just all collectively need to do a little bit better job of saying, all right, this is great. How are we going to use it? What are the guardrails, right, and where should they be? Look, we don’t let children drive a car until they’re 16 years old. They have to pass a test. And in most states you have to have a chaperone for a number of years and even then your insurance is through the roof for another eight or nine years. Right? The actuarials at accounting, people in auto insurance companies were way ahead of the brain science they knew the prefrontal cortex and the brain didn’t mature until the mid twenty s a long time ago. They could just look at the automobile records. Right. So why do we give an eight year old a supercomputer in their pocket that’s more powerful than what put the person on the moon with access to the entire world’s Internet at the push of a button? It’s a bad idea. It’s a bad idea.

Roger Dooley [00:22:52]:

Right? Well, it kind of gets to the Google effect, which you mentioned in the book, where Google has undoubtedly been a massive productivity enhancer. I mean, I can’t imagine writing a book pre. A lot of books are written pre Google. I know, but today, going back to doing that research in dusty libraries and journals, and it’s not in this library, it’s in another library. And no, I don’t want to go back to that. But you point out that Google has changed our brains too, right?

Carl Marci [00:23:21]:

Yeah. And I think, again, it’s another good example at the point at which the ability to process and use information far exceeds our brain processing speed is where we start to getting into these tipping points. And we’re there, right? We’re definitely there. So I had the same thought as I was writing this book. I was like, how could I not do this without PubMed and access through you mentioned Harvard Medical School having an affiliation to the world scientific literature. Right. It would have taken me ten times as long to write this book. It was amazing, the ability to do that. So that’s a good example of technology facilitating a human endeavor, and I’ve got no problem with that. I think again, the problems start to seep in when you hear statistics like this. And I heard this the other day, and I’m still trying to get my head around it. But from roughly 2000 to 2020, the number of adult Americans who reported that they do not have a confidant or best friend in their life went from 2% to 12%. That’s a ten X increase, almost. Right. And so you say, all right, well, that’s a pretty big number. When you then look at millennials, one third one out of three millennials say they do not have a best friend or a confidant. That is, to me, a staggering number. Right. And is part of why we’re seeing a lot of mental health issues. So to answer your question about why I wrote the book, part of it was I had a front row seat to the introduction of the interscope was found in 2006. The atom splitting moment when Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone was 2007. Right. And the big media companies were hiring us in 2008, 910 and eleven to figure all this stuff out. And so I saw all this stuff early and have had a lot of time to think about the mental health implications of what I describe as an uncontrolled experiment with technology on a global scale.

Roger Dooley [00:25:17]:

Carl, what are superstimuli?

Carl Marci [00:25:19]:

I stumbled on this research on super stimuli. And this goes back to the there was a researcher in Europe who ended up, I think, winning a Nobel Prize for the work, who realized that from an evolutionary perspective, there were some stimuli that were so powerful that we would ignore the innate need that they were based on in lieu of an artificial version of that stimuli. So the classic examples which I give in the book are certain songbirds who will ignore their own eggs that are speckled in a particular pattern for a big fake one with even bigger speckles because their brain is wired to say, see, speckles bigger, better, and we’ll go sit on an artificial egg. Or beetles that will climb over a beer bottle instead of mating with the opposite sex that they’re genetically wired to mate with. Even in their presence, they will ignore them. So I started to think about, well, surgically enhanced women and photographs of luscious food and all these things online. I mean, the filters of social media create these curated super stimuli that are very hard for the brain to ignore, and that is driving a lot of these issues. And you have to make a distinction between titillation and healthy reward. And if we’re all just running around getting titillated all the time and this is why young people are so much at risk, because they just don’t have a fully developed prefrontal cortex and cognition to say, wait a second. I just spent an hour and a half looking at cats and dogs doing stupid tricks. That may not have been the best use of my time. I’m just making that example up. But you see what I’m saying?

Roger Dooley [00:27:13]:

Carl, how can people find you and your ideas online?

Carl Marci [00:27:16]:

Yeah, so I’ve got a website. It’s called https://Rewiredthebook.com . The only social media platform I’m now spending time on is LinkedIn, so please feel free to reach out and follow me there. I do try to post and put things out there, and then, of course, you can buy the book on Amazon or most bookstores, and I encourage you to do so.

Roger Dooley [00:27:34]:

We will link to those places on the Show Notes page at https://rogerdooley.com/podcast , and also on our YouTube channel for being on the show. It’s been great catching up.

Carl Marci [00:27:46]:

My pleasure.

Outro [00:27:47]:

Thank you for tuning in to Brainfluence to find more episodes like this one and access all of Roger’s books, articles, videos, and resources. The best starting point is RogerDooley.com. To check availability for a game changing keynote or workshop, in person or virtual, visit RogerDooley.com.